The Los Alamos Primer

Part 1

I recently watched a lecture on how nuclear weapons are designed. It mentioned a few reading recommendations for anyone wanting to learn more, and one of those was The Los Alamos Primer. The primer itself is interesting for several reasons: it’s pretty old (mid 1940s old) and it’s based on five lectures Robert Serber gave in early 1943. If you open it up, you’ll see it’s very direct and technical, jumping right into things from the very first paragraph:

The object of the project is to produce a practical military weapon in the form of a bomb in which the energy is released by a fast neutron chain reaction in one or more of the materials known to show nuclear fission. It was classified for a long time but is now available publicly. Due to its historical and academic context I was sure I wanted to read it.

Quick heads-up if you’re thinking of buying a physical copy: I don’t recommend the paperback with the portrait on the cover (possibly Serber?). I ordered it on Amazon, and it turned out to be a low-effort print of the public-domain PDF on flimsy paper. Honestly, the online PDF is easier to read.

Why This Write-Up?

I’m writing this partly to solidify my own understanding, and partly in case it helps anyone else working through the Primer. The text often skips steps, uses outdated notation, and can be pretty dense. Filling in missing context and modernizing the explanations felt worthwhile.

Units

One thing to keep in mind: the Primer uses the centimeter–gram–second (CGS) system units instead of SI. That means centimeters instead of meters, ergs instead of joules, and so on. The differences aren’t huge most of the time, but it’s easy to get tripped up if you’re used to SI.

Terminology

The Primer also avoids naming elements directly. Uranium-235 becomes “25,” Uranium-238 becomes “28,” and plutonium is called “49.” At the time, the name “plutonium” may not even have been finalized yet. It gives the whole thing a slightly cloak-and-dagger vibe.

Energy of the Fission Process

The Primer starts with some back-of-the-envelope estimates for energy released per fission, assuming roughly 200 MeV per atom. One calculation they show is:

Two things to point out:

- I'm not entirely sure where the factor of

We then take the weight of one nucleus to be

Fast Neutron Chain Reaction

Things ramp up quickly here. Since each fission releases about two neutrons, the neutron population can grow exponentially.

- The Primer makes two idealized assumptions to keep the math simple:

- No neutrons escape the material

The material is perfectly pure, so none are wasted on other reactions

Under those assumptions, they estimate roughly 80 neutron generations to fission a kilogram of U-235.

In reality, neutrons do escape, especially near the surface. If we model the fissile material as a sphere, neutron loss scales with surface area, while neutron production scales with volume.

At some point, surface losses overpower neutron production and the chain reaction dies out.

The key question becomes: does the critical radius grow faster or slower than the sphere expands under explosive pressure?

If the reaction outruns the expansion, you get an explosion. If not, the material blows itself apart before fully fissioning.

Another interesting note: each nucleus releases so much energy that even if only 0.5% of the available energy is released, the material’s temperature skyrockets to about

We can sanity-check the Primer’s temperature and particle-speed estimates with some rough calculations.

Temperature

We take the

Mean speed

Given we have double the energy available (i.e. 1% vs 0.5% from the last example) we have 8.5 keV per nucleon. Taking the mass of one to be

There are two key points to take in from this.

-

The entire fission process has to happen extremely fast. If criticality is lost after ~5 cm of expansion, the reaction must complete in roughly

-

Slow neutrons are effectively useless in this regime - they simply don’t act fast enough.

Fission Cross-sections

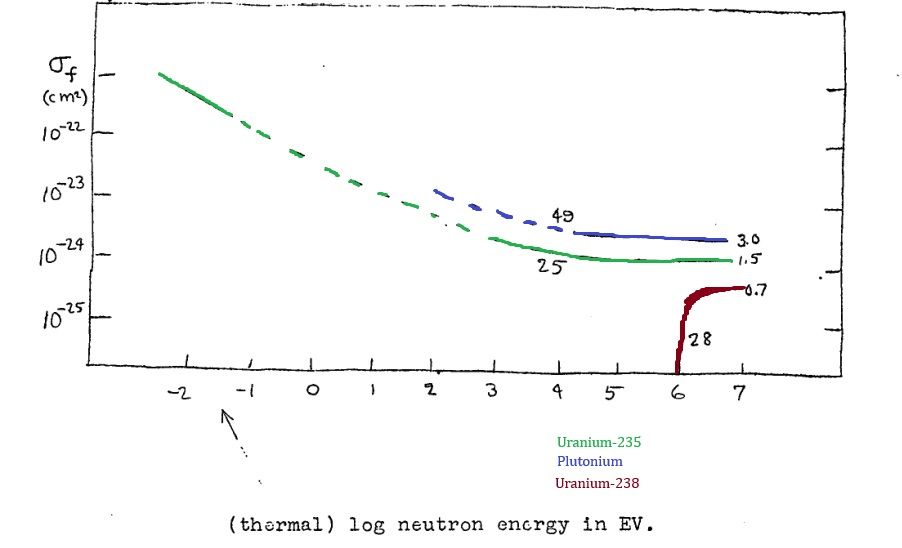

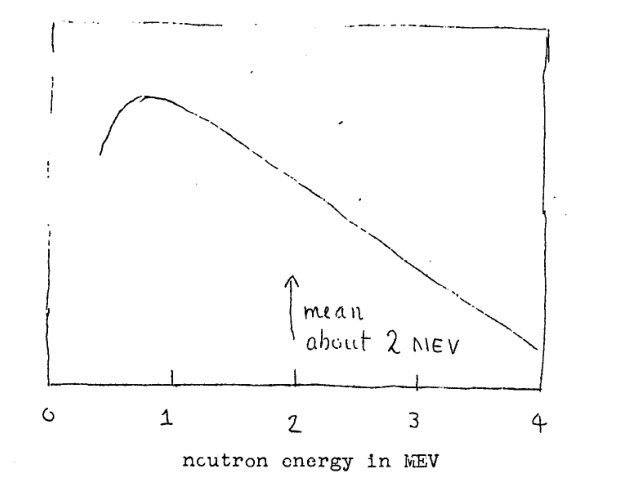

The Primer includes cross-section plots for U-235, U-238, and plutonium. The key point is that U-238 (which is 99.3% of natural uranium) only has a significant cross-section above about 1 MeV. Another graph shows the energy distribution of neutrons released in fission. Most fission neutrons do have energies around 1 MeV or higher, but not all stay that energetic for long.

Neutron number

The neutron number

Why ordinary uranium is safe

Since U-238 makes up about 99.3% of natural uranium, the Primer points out two reasons it can’t sustain a fast chain reaction:

- Only about 3/4 of generated neutrons will be above 1 MeV.

- About 1/4 of those neutrons are lost before they can cause fission.

Starting with an initial neutron number of

Note

I'm happy to accept the 3/4 factor: it seems sensible enough given the neutron energy distribution and the cross section plot referenced earlier. I'm sure we'll have far more accurate data on both now but we're trying to work off what was available at the time.

I've tried to run simple simulations to work out where the 1/4 factor is coming from but I was getting wildly different results. I.e. I wanted to work out the chances of a neutron causing a fission reaction BEFORE it's slowed down below ~1MeV level. This means factoring in inelastic and elastic collisions with their respective probabilities. However, I think there might be a few key factors missing from my attempts:

- The cross-sections are energy dependent

- The inelastic cross-sections vary with energy and have thresholds

- Even elastic scattering changes with energy

- The geometry matters too

- The actual path length through the material

- The probability of leaving the material entirely

- The effects of spatial distribution

- The end probability of being slowed down will depend heavily on the starting energy as well

In the end I'm not sure where the 1/4 factor is coming from. It's likely a very conservative estimate based on limited experimental data available at the time and some simplified calculations that could be done without computers.

Making plutonium

Section 10 of the primer talks about "element 49" which we now know as plutonium. At the time the notes were written only minute amounts had been created though. The section ends with:

since there is every reason to expect its

to be close to that for [uranium] and since it is fissionable with slow neutrons it is expected to be suitable for our problem and anothor project is going forward with plans to produce it for us in kilogram quantities. Further study of all its properties has an important place on our program as rapidly as suiteable quantities become available.

Spoiler alert: they eventually did produce plutonium in kilogram quantities and used it in Fat Man.

TBC

I’ll stop here for now. In the next post, I plan to dig into the Primer’s discussion of minimum critical masses, tampers, and their early damage estimates.