Why the Liar Is the Helpful One

In logic puzzles, lies can be more useful than truth.

That sounds backwards. In everyday life lies obscure things. In formal logic, though, a false statement can be much more constraining than a true one. Knights and Knaves puzzles are a neat playground for seeing this happen in real time.

I'm writing this as someone who enjoys these puzzles, not as a logician - corrections welcome.

The rules

Knights and Knaves are puzzles with a very simple premise. They only involve two types of people:

- knights always tell the truth

- knaves always lie

Every puzzle is just different combinations of statements made under those constraints. They come in different flavours: e.g. there's a Gods, Mortals and Demons [1] version where Gods are the Knights, Demons are the Knaves and Mortals are 50/50: they sometimes lie and they sometimes tell the truth.

I'm not entirely sure about the origin of the name (I think the concept itself is very old) but I know that they were popularised by Raymond Smullyan in his various puzzle books. They're not realistic (indeed what puzzle is) but they're very fun to solve. The key to solving them is to play "deep": all the statements made by different people always relate to one another in some way, and we have to follow the links until we've whittled away all the non-possibilities.

A puzzle where lying is good

Here's an abridged[2] version of a puzzle inspired by Smullyan[3].

Inspector Reynolds is searching for the fountain of youth on an island inhabited only by knights and knaves. He meets two people, A and B, and asks whether the fountain is on the island.

They say:

- A: If B is a knave then the fountain is on the island.

- B: I never claimed that the fountain is not on the island.

Reynolds asks again, "Is the fountain on the island?" One of them answers YES or NO. We're told that after hearing that single answer, Reynolds knows the truth.

Later, Reynolds tells this story to a friend. The friend says they still can't determine the answer, because they don't know who responded or what they said. Reynolds is asked by the friend if he knows whether or not he could have decided the answer had the other person answered. They get a reply, and say "I now know if the fountain is on the island".

Is the fountain actually on the island?

Show HINT

Consider what B's statement actually means, and how it relates to A's statement.

If you'd like to solve this yourself please do it before reading ahead

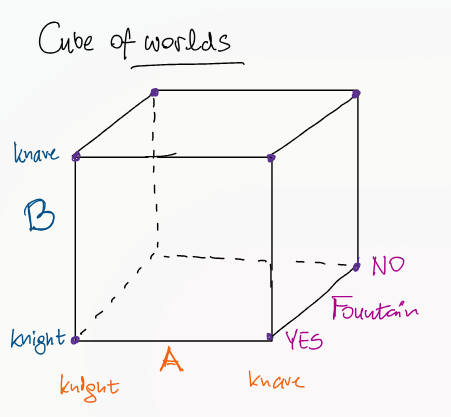

Before we begin: we have 2 options each for A and B's types, and 2 options for whether the fountain is on the island. That gives us 8 possibilities total (2×2×2). Yes, I know that some of these are impossible: that's what we'll be working out next.

| A role | B role | Fountain on island? |

|---|---|---|

| Knight | Knight | Yes |

| Knight | Knight | No |

| Knight | Knave | Yes |

| Knight | Knave | No |

| Knave | Knight | Yes |

| Knave | Knight | No |

| Knave | Knave | Yes |

| Knave | Knave | No |

You can think of this as a tiny constraint satisfaction problem.

A "world" is just an assignment of values to three variables:

- A

- B

- F

Each statement we hear introduces a constraint that eliminates some assignments. Solving the puzzle means intersecting all those constraints until only consistent worlds remain.

At the start we have 8 candidate worlds. Every piece of reasoning we do from now on is just model elimination: throwing away the worlds that violate the rules.

Let's first think about what B is saying.

If B is a knight then their statement is completely trivial and gives us no information whatsoever. They're telling the truth: they never claimed that the fountain isn't on the island. Even if the fountain WERE on the island this is of no help to us.

A side note: in these puzzles, statements like "I never claimed X" are treated purely as logical objects, not as inspectable personal histories. A knave uttering that sentence must be making a false statement, which logically entails that they did claim X at least once. We reason about the truth conditions of the sentence itself, not about reconstructing a backstory. So, assuming B is a knave is completely different: they're lying, so they must have claimed at least once that the fountain isn't on the island. But then again... they're a knave, so they always lie. So that original claim must have been a lie, i.e. the fountain is indeed on the island.

Notice that B's sentence gives us a standalone constraint:

Lemma. If B is a knave, the fountain is on the island.

If B is a knight, we learn nothing. If B is a knave, the lemma already forces the fountain to exist. In that sense A's implication becomes redundant in the knave branch.

Specifically:

If you want to see this in propositional logic, we can introduce symbols:

A knave is just the negation of being a knight.

B’s statement gives us the constraint:

A’s statement becomes:

We’re not solving these symbolically, but it’s helpful to see that the puzzle is equivalent to asking:

which assignments of (

, , ) satisfy all constraints?

The table above is literally the model space of this formula.

So the crux of this whole puzzle is A's original implication.

The asymmetry of implication

A says "If B is a knave [then] the fountain is on the island".

Consider a more general statement of the form:

If P then Q

In logic this is an implication, written

The key observation is simple:

An implication is false in exactly one case: when P is true and Q is false.

Three rows make it true, one makes it false. Intuitively, an implication only promises something when the condition is met. "If it rains, I'll bring an umbrella" says nothing about sunny days.

Truth leaves many worlds open; falsity leaves almost none. The reason this asymmetry exists is vacuous truth. An implication is automatically true whenever its condition is false. That means a true implication is compatible with many different worlds, because it doesn’t force the condition to hold. A false implication, on the other hand, pins reality into a single narrow shape.

One lie gives us two hard facts. Falsity is a tight box for implications. A true implication corresponds to a large set of compatible worlds. A false implication corresponds to a very small set.

This is the engine that powers a lot of Knights and Knaves reasoning. Assuming someone is lying often collapses the search space much faster than assuming they're honest.

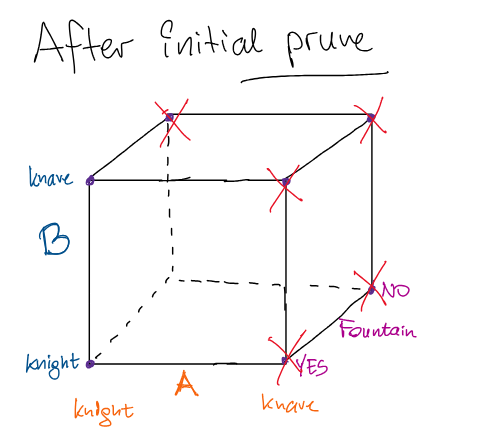

Applying this to the puzzle

We can have A be a knight or knave. Assume A is a knave. Then (as explained above) that actually means:

- B is a knave

- The fountain is NOT on the island.

Just one statement would be enough to identify the one true reality from all 8 possibilities!

Yet from the lemma above, B being a knave implies the fountain is on the island. But we just established that if B is a knave, the fountain is on the island. Contradiction. So A cannot be a knave.

From now on we can assume A is a knight.

By considering the implication (particularly what it would take for it to be false) we can throw away 5 possibilities:

- 4 possibilities where A is a knave

- 1 possibility where B is a knave and the fountain is NOT on the island

We're down to 3 possible worlds:

- A and B are knights, fountain is on the island

- A and B are knights, fountain is NOT on the island

- A is a knight and B is a knave, fountain is on the island

Constraints, not honesty

Knights and Knaves puzzles aren't really about truthfulness in the everyday sense. They're about how logical constraints propagate.

A truthful implication leaves multiple worlds open. A false implication slams almost all of them shut. When someone lies in these puzzles they are really handing you a statement that cannot be true. For implications, "cannot be true" is an extremely narrow target.

That's why assuming someone is a knave often feels like cheating. You're exploiting the fact that falsity carries more information density than truth in this system. This pattern shows up far beyond recreational puzzles. SAT solvers, type checkers, and constraint engines all work by eliminating impossible models. Branches that force contradictions collapse quickly; branches that remain consistent tend to leave large model spaces.

Aside: encoding this in Prolog

Another satisfying way to see this is to encode the puzzle in a logic programming language like Prolog. Instead of reasoning informally, you represent each person as knight or knave, encode their statements as logical rules, and let the solver eliminate inconsistent worlds.

What feels like intuition while solving by hand turns into brute-force pruning of a search space. The same asymmetry shows up: the branches where an implication is forced to be false collapse almost immediately.

Here's a minimal model of the puzzle:

:- use_module(library(lists)).

% valid_world(A, B, F)

% A = type of person A (knight or knave)

% B = type of person B (knight or knave)

% F = fountain status (yes or no)

valid_world(A, B, F) :-

member(A, [knight, knave]),

member(B, [knight, knave]),

member(F, [yes, no]),

% At this point Prolog is iterating over all 2×2×2 = 8 worlds

% A says: "If B is knave then F is yes"

% Logical form: (B = knight) OR (F = yes)

((B = knight ; F = yes) -> AStmtTrue = true ; AStmtTrue = false),

% Knights tell true statements, knaves false ones

(A = knight -> AStmtTrue = true ; AStmtTrue = false),

% B says: "I never claimed the fountain is not on the island"

% If B is a knave, that statement must be false, which forces F = yes

(B = knave -> F = yes ; true).Querying valid_world(A, B, F) returns our three surviving worlds:

A = knight, B = knight, F = yes ;

A = knight, B = knight, F = no ;

A = knight, B = knave, F = yes ;

This snippet stops just before the meta-reasoning. If you want to see a full Prolog solution including the Reynolds/friend dialogue, see my gist. (Full disclosure: I had LLM assistance finalising it - I haven't used Prolog in years.)

The meta-reasoning

Now we need to figure out who answered Reynolds and what they said.

We have 3 possible worlds and 4 possible answers (A says YES, A says NO, B says YES, B says NO). The three possible worlds:

World 1: A = knight, B = knight, F = yes ;

World 2: A = knight, B = knight, F = no ;

World 3: A = knight, B = knave, F = yes ;

The key constraints are:

- Reynolds knew the truth after hearing the answer

- The friend could determine the truth after hearing whether Reynolds could have decided if the other person had answered

Full case-by-case analysis

At this stage the puzzle becomes epistemic[4]: it’s about who knows what after hearing which answer. In this context, knowing means that the answer uniquely identifies a single remaining world.

In all possible worlds A is a knight, so if A answers, Reynolds learns the truth directly:

- A says YES -> fountain is on the island ✓

- A says NO -> fountain is NOT on the island ✓

If B answers NO, Reynolds can't be certain: it's consistent with World 2 (B is a truthful knight, no fountain) but also World 3 (B is a lying knave, fountain exists). Since Reynolds did know the answer, we know B didn't say NO.

If B said YES, we know we're in World 1. Here's why: in World 2 (no fountain, B is knight), B would truthfully say NO. In World 3 (fountain exists, B is knave), B would lie and say NO. Only in World 1 (fountain exists, B is knight) does B say YES.

So we have 3 cases where Reynolds knows the truth after his second question:

| Case | Who answered | Answer | Fountain? |

|---|---|---|---|

| X | A | YES | Yes |

| Y | A | NO | No |

| Z | B | YES | Yes |

Now, when Reynolds's friend asks "do you know if you could have decided had the other person answered?":

- Case X: A said YES, which puts us in World 1 or World 3.

- other answer is B: YES -> Reynolds would know (World 1)

- other answer is B: NO -> Reynolds would NOT know (World 3)

- Case Y: other answer is B: NO -> Reynolds would NOT know (could be World 2 or World 3)

- Case Z: other answer is A: YES -> Reynolds would know (World 1)

In Case X, Reynolds can't know up front which answer he'd get from B. He would not have been able to deduce either way. He would have to say "No, I don't know if I could have decided." In case Y we know that B would say NO, but similarly, that can put us in either World 2 or World 3. Reynolds wouldn't know which one was true - BUT he'd know that he couldn't have decided. I.e. he could say "I know if I could have decided (for I know I couldn't)" In case Z we'd hear back from A and could trust their answer. Reynolds would know in this situation, so he'd say "Yes, I know if I could have decided (for I know I could)."

So if Reynolds says "Yes, I know if I could have decided had the other person answered" it means we're in either Case Y or Case Z. If Reynolds says "No, I don't know if I could have decided" -> we're in World 1.

Since the friend says they now know the answer, we know Reynolds said "No".

The rest is bookkeeping - working through who said what. I'll spare you the full enumeration (it's in the collapsible above) but the upshot is: after working through all the cases, the friend could only determine the answer if Reynolds said "No, I don't know if I could have decided had the other person answered." This pins us to World 1: both A and B are knights, and the fountain is on the island.

You can summarize the whole phenomenon as a small rule:

True statements preserve many models; false statements destroy most of them.

Knights and Knaves puzzles are interesting because they let you watch that rule operate in slow motion.

Summary

In Knights and Knaves puzzles, assuming someone lies often gets you further than assuming they're honest. A true implication leaves many worlds open; a false one collapses nearly all of them.

In fact these are usually way more interesting than the "vanilla" version. ↩︎

After writing this I'm not sure if it's actually abridged at all compared to the original. Then again - there's quite a lot to communicate here. ↩︎

I got the puzzle from "To Mock a Mockingbird and Other Logic Puzzles" (1985) by Raymond Smullyan. It's the last puzzle in the Knights and Knaves section. The second half of the book covers combinatory logic. ↩︎

BIG word but I think it's correct in this context... ↩︎

- ← Previous

How to mount a WSL2 disk on Linux - Next →

Dark Alley Mathematics